“I’m staying in a hotel with a four-poster bed,” the text read.

A four-poster bed. That’s where he hung, the only witness to his last breath until death closed his eyes a final time.

Or were his eyes open as he swung?

Was he far from the ground? Did his feet hang down?

Was he barefoot, clothed?

Did his hands reach up to his throat in regret at the rope?

What was his last booze-soaked meal on this earth?

What was the last thing that touched his tongue – Scotch with a side of valium?

That tongue must have hung like his sons’ when he too choked himself of his breath.

You ask how my father died.

Do I lie or say it was suicide?

Do I reward your morbid curiosity with this moment of violence?

He hung himself from his four-poster bed.

When you ask why, with your eyes opened wide, I wonder how to refine a life of 59 years down to a few simple words.

Do I say that he was never the same after his son’s life came to an end?

That whiskey was his solace, his poison and his friend?

A self-made man, Dad bought his first house at age 21 on a graduate teacher’s salary. That’s how the market was in those days. Evenings spent in the library learning DIY and weekends at hardware stores, Dad refused to pay anyone for anything. “There’s no such word as can’t,” was a classic Steve maxim. “Think positive,” was another. He borrowed against the equity to buy a second property, then a third, filling every spare inch with dead-beat tenants paying dirt cheap rent. The sunroom became a bedroom by simply ignoring that it was the front entryway. A child’s treehouse was soon a backpacker’s bargain loft. Furniture was fixed up from footpaths, the Trading Post and the tip.

My brothers disinterested, I became Dad’s tiny apprentice. Together we changed brake pads on cars and washers on taps; we painted and hammered and dug. Dad’s plan was for me to become an independent woman who wouldn’t get ripped off by Tradies. His shed was meticulously systematised, labelled and stocked up in bulk; WD40 an elixir. His haste led to frequent injuries that did nothing to slow him down. My father’s all season uniform: a cap, thongs and paint-splattered stubbies, and on occasion, an unbuttoned checked shirt and tennis shoes.

Dad fitted out his properties with pool and ping pong tables, creating communities of potheads, pissheads and travellers. Once you were in the system it was near impossible to leave; there was simply no better deal. Tenants would get as far away as Steve’s next property two streets over. My brothers and I all fell into the trap once we started renting.

Every house was painted the same colonial colours: cream with green and maroon accents, complete with a 6 foot fence and a plasterboard deck. This was his formula and he applied it indiscriminately.

The house he lived in for 20 years was not immune: an old Queenslander on stumps he raised to build underneath. He converted the wrap-around veranda into self-contained living quarters, thereby extinguishing all natural light from his loungeroom. Windowless walls were swallowed up with clutter from dusty tennis trophies to travelling photos to knickknacks on boxes of junk.

Thynne Ave went from a two bedroom one bathroom property to seven bedrooms two bathrooms. This wasn’t bringing in quite enough income so Dad hauled in a couple of old caravans, running extension leads from the house through the mango tree. Up to 12 people lived there at any given point. Ever the entrepreneur, Dad supplied his captive market with weed on the sly.

A typical Thynne Ave tenant was Terry, who inherited $200k on his 18th and spent the next 5 years bludging off it. He ventured no further from his room than to the local fish ‘n’ chip shop. Dad’s properties kept that place in business. Terry’s inheritance funded his online gaming habit, pizza predilection and coke addiction – the bevvie. Such were his personal hygiene habits that Terry’s skin came off in green flakes.

At McIlwraith Ave were Shebaware and Tebaware, nicknamed by my brother Mikey for their incomprehensible stutters. Mac Ave was a huge Queenslander turned block of six flats. The bearded brothers – Shebbie and Tebbie for short – shared flat three. They never desexed their cats so there were soon dozens of pungent kitties roaming round the joint. Next to them was a mulleted bogan ex-con called Snake. Snake had a charming habit of brandishing swords and threatening neighbours when drunk, which was daily.

Another tenant was Dave (not-so) Bright, a junkie who did odd jobs for Dad in lieu of rent, except that he never got anything done. Bob the Builder was also recruited to the tenant taskforce. Bob’s finest work was to raise a house of Dad’s to well below legal height, plaster round pipes that poked through the ceiling, and install a lime green chipboard kitchen fresh from the dump. With a rampant betting addiction, Bob regularly hocked Dad’s power tools, so it wasn’t the most economical partnership. But Dad believed in second chances. Tenth chances too.

Given how commonplace it was for his belongings to go missing, Dad took to sprinkling fingerprint dust on his window-sill and labelling everything ‘STEVE’. This included meticulously sticky-taping tiny tags onto every single pen he owned. On a job once he came across a man he’d never met with a STEVE pen poking out of his shirt pocket. To this day Dad’s name still pops up on extension leads and appliances throughout the family and beyond.

Dave Cotterall was a recluse who responded to requests for rent by threatening Dad with a knife. As a life-preserving measure Dad thought it best to find alternative accommodation and a factory job for Dave. Clearing out the caravan upon Dave’s departure involved throwing away litres upon litres of piss: evidently Dave hadn’t left his caravan to walk two metres to the toilet.

In ‘98 Dad cottoned on to the fact that dead-beats weren’t necessarily the best nor safest source of rental income, opting for foreign students instead. Barbies on the back deck became a memorable Steve tradition. We’d toast cheap goon in the spa. He was the king of his empire, rattling off phrases in Korean and handing out the lyrics to our national anthem for compulsory sing-alongs.

Well into the 21st century Dad collected rent in person and gave paper receipts, committed to covering up the extent of his overcrowding. ‘Dodgy Dad’ opened bank accounts in fake names, siphoning off money to avoid paying taxes and to screw our mother in the divorce settlement. Money was a life-force, imperative. Dad’s mania would often manifest as money-making schemes, like the time he bought two dozen tanks full of guppies to breed and sell. His ‘nervous breakdowns’ coincided with stock market crashes and the second left him bedridden. Mum had no choice but to return to work and leave Dad in charge. One time he left us alone at the beach all day without sunscreen, the summer heat searing. We were aged 3, 5 and 7. “Don’t worry Mum,” her eldest proclaimed proudly. “I was looking after the kids!” Mum finally decided she had to leave after a neighbour reported that we’d been left out in the yard all week without food or water.

After we moved out, Dad filled his spare time by acquiring a second full-time job. It became was one of his many didactic moments. “Rest is good,” he would tell us, closing his eyes at traffic lights till the cars behind beeped. “Shade is good,” he’d proclaim, every time he pulled in to a parking space. A former science teacher, Dad worked in a paint factory by day, and drove taxis all night. “If you can’t do what you love,” he’d say, “then love what you do.” Not out to win friends, he regularly skipped the taxi queue to swipe passengers.

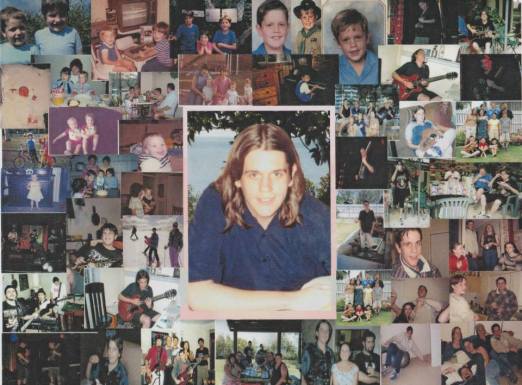

He was very proud of this photo.

Every second weekend we stayed with Dad at Thynne Ave. He’d tuck us in to bed and head out in the taxi, leaving his most trusted tenant in charge – a paranoid deaf-blind guy named Parker. One night we played the Commodore 64 till sunrise and realised there was sand in our eyes despite no visit from the Sandman. When Dad arrived home, we all piled into his waterbed to watch Rage video hits and hear his latest taxi tales. “He had what looked like a gun pointed at me,” Dad recounted, “and he goes, ‘gimme all ya money!’ I pretended not to hear ‘im. I just pulled over, switched off the meter and said, ‘that’ll be $19.40 mate.’ There was a tense pause, I repeated the fare, and you wouldn’t believe it but he handed over 20 bucks and jumped out!”

To me, Dad was heroic. He could do anything. He’d tie rags over the frame of his racer for little me to sit side-saddle as he powered up the hills of Norman Park. When I reached hip height he taught me to ride a bike of my own. When I reached shoulder height he taught me to drive. My practice vehicle was Dad’s prized piece of shit: a back-firing column-shift van. Dad ran a delivery business and owned a fleet of 11 such bombs, employing the very same tenants to ensure they could pay rent.

Time was money, seat-belts redundant. For maximum efficiency, every van was carefully subdivided into 12 specifically identifiable areas, such as ‘left back near’ and ‘upper right far’. “You’ve got to have a SYSTEM Nic-Jane,” he reiterated regularly. My run was a maze of one-way streets which required constant reversing. Groceries obscured the rear-view. Dad would gently calm my nerves by shouting, “fucking indicate!” A family day at the beach involved me behind the wheel with Dad yelling, “MERGE RIGHT!” as we entered the motorway. “But I’ve never even changed lanes before!” I cried back through tears.

Even as children we found our father parody-worthy: “Get in the car I SAID get in the CAR I SAID-“ we’d mimic, with rapid smacking sound-effects to highlight his impatience. Everything was always urgent with Dad – I had to jog to keep up with his brisk walking pace – until the days when his depressions grew longer and deeper.

Dad bought his little girl her first car – a Toyota Corolla that came free for parts. Despite the Fred Flintstone-esque rusted flooring I was proud of my cute gold hatchback. On its virgin tour my beloved steed filled with chemical smoke so thick I couldn’t see my cousin in the passenger seat. We all staggered out coughing and spluttering worse than the car itself. Upon inspection my cousin discovered dodgy wiring hooked up to a truck battery in the boot. My father was nothing if not inventive, a real Aussie MacGyver.

Freshly licensed, I had three accidents in three weeks. “Someone must’ve backed into me in the car park again, Dad!” I would insist. He indulged my blatant fibs with a half-smile.

The Corolla a death-trap, I soon graduated to a Daihatsu Charade. Dad bought it cheap from a guy named Sergio who hotted it up on a shoestring. The Charade was a bogan chariot with an exhaust muffler tip for maximum audio; plastic DIY bonnet scoops and absolutely nothing spent under the hood. All bark and no bite, it would roll backwards up hills with the accelerator flat out. The engine would even cut out mid-drive. Thankfully I got mildly t-boned at an intersection and the car was written-off. At this point my mother ardently petitioned Dad to buy his only daughter a car that was actually road-worthy.

Dad didn’t subscribe to standard gift-giving for Christmas and birthdays, preferring to buy practical presents when there was a bargain to be had. Early on Dad revealed the truth about Santa’s non-existence, swiftly solving that hassle and expense. For Father’s Day he only ever wanted cashews and cigars, feigning surprise whenever he tore open the wrapping paper. Dinners were carefully apportioned and labelled for each day of the week. Family meals out were contingent on discount vouchers, most often at the Casino.

More than gifts Dad gave us memories: motorbikes and biplanes and camping on Moreton; hiking in a rainforest till we were covered in leeches; kayaking and sailing on the filthy Brisbane river; shooting cans on the farm and riding the quad; playing corners in the car on trips to the coast. We spent weekends playing tennis to a strict warm-up schedule, or barbecuing and jetskiing, getting flipped off kneeboards and rubber rings. Tenants could join of course, if they chucked in for petrol. On the sport jetski Dad did tricks to impress the crowds, breaking his nose on the handlebars one time. For long-distance trips on the three-seater he didn’t see the need to carry excess weight like enough fuel. A shameless, shirtless Dad would simply jump ashore and ask around.

To my father’s great pride and dismay, I inherited his spirit of adventure and longed to travel the world.Dad had visited every continent on earth except Antarctica. In manic moments he’d insist he would live to 150 and visit the moon; I almost believed him.

Dad’s ‘time is money’ motto extended to his travels, like when he drove round Australia in 6 weeks, an ambitious feat that takes most people months. His trick was to divide the nights into shifts with my step-mum to cover the k’s. It goes without saying that he fitted out the utility van himself. Another time he bought a rusty 4WD for a road-trip to Cape York, the most northerly tip of Australia. After 6,000 kilometres of red earthed beauty, through treacherous terrain and croc-filled waterways, past abandoned vehicles that couldn’t make it, he resold the 4WD for a tidy profit.

One year Dad pulled us out of school to drive down south to the snowy mountains. Our true education. Home video footage shows a 7 year old me lying in a tangle of skiis while Dad coaches me into getting myself up. “There’s no such word as ‘can’t,’ Nic-Jane,” he says. Another clip shows my brother AJ skiing down a slope chatting to the cameraman, Dad, who is saying, “I’m fine, I don’t need poles.” Moments later a massive ditch comes into view and both Dad and AJ go flying. On the drive home we stopped at the Big Banana; our little faces lisp away at the camera, blistered from the harsh Aussie sun reflecting off the snow.

The year before, Dad took us on a grand voyage to Disneyland. No time for preparations like remembering to bring cash or cards, we spent the first night in a homeless shelter in Los Angeles. Once money was wired over Dad took us for a fancy meal at KFC to celebrate, inviting a toothless man named Bub to dine with us and get in the family photo. The following evening we ate biscuits for dinner in the motel while Dad popped out to see the local sights of downtown LA, almost getting mugged in the process. Our road-trip took us from Los Angeles to Las Vegas where we got busted for playing slot machines in a 7-Eleven. From casinos to the Grand Canyon, we awoke at dawn for the long trek down. “Think strong, Nic-Jane,” Dad said when I whinged about my tired little legs. “There’s no such word as can’t.” To reinforce the lesson (and save a few bucks) he refused to hire me a donkey.

Next we drove through the Arizona desert, a country music mixed-tape blaring, illegally picking cotton, throwing fool’s gold through cacti, and singing a song about a dead skunk. In a ghost town from the gold rush era we drank root beer. Total population: a guy named Pop. Down into Tijuana we travelled to smuggle tequila from the slums across the border. “Did y’all enjoy Mexico?” a border guard asked us. “It stinks!” Mikey answered, age 7.

These adventures shaped me. Not long before I moved to London and broke Dad’s heart, we rode bikes to the tennis courts. It was just us two, just like the old days, fruit bats screeching overhead. We played till it stormed and we laughed till it hurt and the world felt limitless.

In the weeks after my brother died Dad would introduce strangers to his son, an A4 framed photo of Mikey propped beside him in the van.

Mum invited Dad to a Survivors of Suicide support group, where he proceeded to take over, make impolite remarks and piss everyone off. Bipolar and bereavement didn’t make him the most cooperative group member.

Our last DIY project together, long before London, was painting McIllwraith. I’d shared one of the flats with Mikey before he hung himself out back. Part of Dad’s property plan had been to have all his kids close. Now he wanted McIllwraith gone. Thynne Ave too. All those memories. A slimy real estate agent took advantage and sold both for a loss. Dad was still into second chances, to a fault.

After a failed suicide attempt of his own (hose pipe, van), I flew back home to Brisbane. It was hoped that my presence would snap Dad back to reality. No pressure!

I was also visiting to help get his remaining properties ready for sale. A once successful business man and former owner of up to 5 properties, my father was now bankrupt. With a gambling addiction worse than Bob the Builder’s, he was a million dollars in debt. His only prospect was to share a house with green-scaled Terry that in better days he’d sold to my brother.

Several times he admitted himself to hospital complaining of heart troubles; the doctors could find nothing wrong with him. His heart was damaged in ways Western tests won’t show. He needed taking care of. A break from life is not what this society offers for free.

One day I managed to get him up, dressed and over to a house I was clearing out for him. Armstrong Rd had been my home for four years. After I moved to London, tenants became squatters; he was unable to collect rent. My brothers and I loaded his van for one final trip to the dump. Scared and broken, Dad mumbled, “I can’t… I can’t.” This from the man who insisted there was no such word.

AJ lost it. “You are fucking pathetic!” he yelled, punching our father’s cowering body. “Why don’t you just kill yourself?”

“Please stop. Please…”

As a moral stance, Dad was against violence of any kind.

Except that his final gift to us was his body hanging from a four-poster bed.

He always had his own way with presents.

I drove him to the doctor’s to get a mental health plan. The GP sent him away with a valium prescription. I confiscated half the pills. That night he phoned me, a once proud man begging.

The dog licked his limp hand the next day. I called the ambulance. They simply discharged him with a hangover. Two weeks later he was dead, hanging from that four-poster bed.

There were notes in his room, mountains of to do lists, affirmations, a few ticked off, most not. Lists upon lists. That urgent, capitalised scrawl on scraps of paper piled next to the bed between packets of pills.

He couldn’t physically button a shirt in the end, pacing and muttering when he was up but he was mostly down in the day. Nights were for haemorrhaging money on the foreign exchange, days were for washing meds down with whiskey to summon slumber.

Notes on his front door reflected his decline:

Steve is not available till 2pm.

Steve is not available till 4pm.

Steve is not available till 6pm.

Steve is not available.

Steve is not